Today sees us at the very end of the known World! So far as was understood by European navigators and explorers in the 14th century anyway. From Modestine’s window tonight we can see the Cabo de São Vicente. This would have been the very last sight of land as traders set sail to explore the vast ocean of the Atlantic and to seek out new worlds and trade routes. The Cabo de São Vicente is a desolate, barren, windswept promontory with a lighthouse, at the furthest tip of Portugal. The coast here is very flat, being nothing but bare rock with a few low bushes and the wind howls across with nothing to break its force. The cliffs fall sheer, forty metres or more into the Atlantic. A solitary, six kilometre long road leads out to the headland and there is almost nothing in the way of habitation beyond the little town of Sagres other than a derelict fort.

Cabo de São Vicente

Cabo de São Vicente Cliff tops, Cabo de São Vicente

Cliff tops, Cabo de São Vicente Atlantic waves pound the cliffs, Cabo de São Vicente

Atlantic waves pound the cliffs, Cabo de São Vicente Sheer cliffs drop 40 metres to the sea, Cabo de São Vicente

Sheer cliffs drop 40 metres to the sea, Cabo de São VicenteWe left our campsite at Olhão this morning, passing through Faro. We had intended to spend the day there, having pleasant memories from an earlier visit. However, towns are definitely best visited by public transport and we didn’t enjoy the prospect of driving through the outskirts and finding a parking place. So we continued on along the coast, by-passing several familiar places until we reached Lagos where we spent several very happy days on our previous visit to the Algarve, with a delightful Portuguese lady called Maria Jesus who spoke no English. As it was still only mid morning we decided to visit Sagres and the Cabo San Vicente before returning to Lagos for the evening. In the event we discovered this peaceful, almost empty campsite on the desolate headland just outside of Sagres instead. Apart from a German camper van and another from Britain – with a number-plate reading T15 OAM (i.e. ‘t is home) there is nothing but a companionable donkey for Modestine to disturb us.

Typical campsite with over-wintering migrants from northern Europe, Olhão

Typical campsite with over-wintering migrants from northern Europe, OlhãoSagres is a low-level, widespread, whitewashed fishing town of 1500 people and is the mainstay of Portugal’s lobster fishing industry. It sits on the edge of the cliffs with steep steps down to its little fishing port. Off shore there are a couple of small but picturesque rocky islands. The little town’s importance in history results from the interest of Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460), brother to the ruling Portuguese monarch. He is reputed to have founded a training school for mariners here at the fort on the headland at the furthest south-west tip of Europe, preparing mariners to set sail in Portugal’s name, to discover and colonise new countries and to develop the wealth of the country through mastery of the seas and control of trading routes.

Sagres viewed from the fort

Sagres viewed from the fort The harbour, Sagres

The harbour, Sagres Fishing boats and offshore islands, Sagres

Fishing boats and offshore islands, SagresWe visited this fort today and despite the wind, it offered several very different experiences. The central area has a huge stone compass probably dating from the 15th century and is said to have been used in the school as a navigational training aid. There are battlements offering perspectives of the cliffs and the ocean. Beyond the fort is a flat bare headland where the cliff drops abruptly away. The force of the waves has worn great caverns into the base of the cliffs through which it roars with frightening force. At one point on the headland we could hear the thunder of an approaching wave beneath our feet followed, after a brief moment of silence, by the sucking gasp as it surged back out again. We were some 20 or 30 metres from the cliff edge and although attempts had been made to wedge rocks into them, there were chasms in the ground at our feet that opened directly into the sea. As the wave crashed beneath the blowholes the plants around the edge swayed and tossed with the power of the wind forced up.

Fort used by Henry the Navigator as a training school for mariners, Sagres

Fort used by Henry the Navigator as a training school for mariners, Sagres 15th century compass rose, Sagres

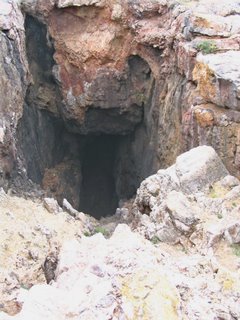

15th century compass rose, Sagres Blow hole on the cliffs, Sagres

Blow hole on the cliffs, SagresThe vital role of fishing to the community of Sagres was brought home to us with a jolt when we saw fishermen with rods and lines, right on the sheer cliff edge, high above the pounding waves in a wind strong enough to lean into. They were bringing up good sized fish hooked to the end of their 40-50 metre lines! They certainly earned their supper the hard way! Looking around the streets of the town later we noticed little groups of weather beaten fishermen relaxing together at the end of the day, happy, smiling, burned by the sun and the wind to look old before their time. The very essence of what this isolated little town is all about.

Fishermen above, Sagres

Fishermen above, Sagres Fishermen below, Cabo de São Vicente

Fishermen below, Cabo de São VicenteTuesday14th February 2006, Luz near Lagos, Algarve, Portugal

During the night we were sleepily aware of the flashing of the lighthouse at Cabo de São Vicente. Strange that the remote ends of those countries forming the Atlantic Arc are all so similar – Land’s End in Cornwall, Pointe de St. Mathieu in Finisterre, the Cabo de São Vicente here in Portugal, and apparently but yet to be visited, Cabo Fisterra in Galicia. All have a landscape of bare rock and low bushes that is eerily beautiful and completely timeless. Most also have megalithic dolmens and have held enchantment for mankind since the dawn of civilization. This area of Portugal reminded us strongly of St. Just in Penwith despite the palm trees and aloes that appeared in any sheltered cleave they could find on this windswept promontory. There are also ancient standing stones to be seen slightly further inland.

We returned to Lagos where we parked near one of the bays to the west of the town to avoid driving into the centre. This enabled us to start the day with a wonderful walk across the cliffs in the bright sunshine, looking down on deserted coves of freshly washed sand with picturesque sandstone stacks, the haunt of seabirds, just off shore. This, according to our French guidebook, is the most beautiful area of the Algarve and we do not doubt it. This part of coastal Portugal is really stunning and its shores being washed by the Atlantic rather than the Mediterranean, it has a damper climate than Spain and is far greener. To our eyes it is infinitely more attractive than many of the areas of Southern Spain we have recently passed through.

Cliff top and sandy beach near Lagos, Algarve

Cliff top and sandy beach near Lagos, AlgarveLagos stood up to our recollection. There has been considerable tourist development since we were here some four years ago but the ancient centre within the city walls is still a lovely maze of cobbled streets and little whitewashed houses and shops. It is of course a major tourist Mecca but somehow has remained reasonably unspoilt.

Aloe, aloe, aloe! Inquisitive chimney, Lagos, Algarve

Aloe, aloe, aloe! Inquisitive chimney, Lagos, AlgarveThere is a fort near the harbour and statues to the Infante Henry the Navigator who masterminded the explorations that set out from Lagos during Portugal’s “Age of Discovery” during the 15th century, and also to Gil Eannes, a 15th century navigator born in Lagos. In the centre of the town we found a rather odd statue to the Portuguese King Sebastian who in 1573 granted Lagos its charter as a city. The statue was erected in 1973 and reflects very much the taste of the day. Is it Luke Skywalker or a Lego man?

17th century fort, Lagos, Algarve

17th century fort, Lagos, Algarve Gil Eannes, Lagos, Algarve

Gil Eannes, Lagos, Algarve King Sebastian of Portugal, Lagos, Algarve

King Sebastian of Portugal, Lagos, AlgarveThe walls of the city are constructed in the Moorish style. The Portuguese recognised an effective and aesthetically attractive thing when they saw it. We were surprised to find they were not built under the Moorish occupation which ended here in the 13th century. Inside the gates is the birthplace of the town’s very own saint – São Gonçalo. We have no idea why he is their saint but, judging from his statue, he appears to have done something miraculous with fishes.

Moorish style gateway – Porta de São Gonçalo, Lagos, Algarve

Moorish style gateway – Porta de São Gonçalo, Lagos, Algarve Coat of Arms and city walls, Lagos, Algarve

Coat of Arms and city walls, Lagos, Algarve City gateway, Lagos, Algarve

City gateway, Lagos, Algarve São Gonçalo, Lagos, Algarve

São Gonçalo, Lagos, AlgarveIn common with so many Portuguese towns, many buildings were destroyed or damaged during the earthquake of 1755 and many of the churches and monuments have been rebuilt since. There are a number of very attractive churches around the town, mostly restrained baroque, whitewashed both inside and out. Altars are elaborate and gilded but far more restrained than we have found in Spain. There are invariably black-clad elderly ladies praying there.

Baroque church, Lagos, Algarve

Baroque church, Lagos, AlgarveWe discovered a less savoury side of the town’s history - the building that had once acted as the slave market, evidence of Portugal’s early trading links with towns along the African coast. It housed the first slave market in Portugal as early as 1441!

Former slave market, Lagos, Algarve

Former slave market, Lagos, AlgarveBeing Valentine’s day we decided to enjoy lunch in the sunshine at a pleasant street café. The young man spoke to us in very educated English with just the tiniest tang of an accent. He let us try ordering in Portuguese, correcting, at our request, both our grammar and pronunciation. The meal was a sort of hotpot of cabbage and potatoes with pork and various kinds of sausage and is apparently typical of the area. It was certainly very substantial! Together with a couple of beers and coffees the bill was 17 euros for both of us. (Around £11.50)

Wandering the back streets we were delighted to discover the house we stayed at on our last visit. Today there was a notice in the window offering rooms to rent. When we were there Maria Jesus had not taken in visitors before and only took us because of a request from her neighbour (we’ll explain it all one day when we put up the blog of that visit). Since then she has obviously recognised an opportunity to supplement her income from her sewing business. We noted her sewing machine is still in the window of her living room.

We walked by the harbour, rediscovering the same caravel that we had seen on our last visit. These are Portuguese 15th century trading ships, the first ships designed to be able to sail against the wind. In the little fort by the marina we saw a video of this very vessel at sea, re-enacting the hard life aboard these tiny ocean-going ships.

Portuguese caravel, Lagos, Algarve

Portuguese caravel, Lagos, AlgarveEventually we made our way back across the deserted cliff top to rejoin Modestine and find a nearby campsite where we are now drinking dark red Portuguese wine appropriately named “Navegante”.

Returning across the cliffs, Lagos, Algarve

Returning across the cliffs, Lagos, AlgarveWednesday15th February 2006, Evora, Portugal

Today we have headed north. Time is moving on faster than we are and there is a serious risk of it running out before we reach northern France for our temporarily return to England.

We had in mind to visit Lisbon, having very pleasant memories of the city when we backpacked around south-west Spain and southern Portugal a few years ago. However, we have come to realise that major cities are not a good idea with a camping car, no matter how small. Backpacking in the countryside and provinces by public transport is almost impossible so we have decided to concentrate on what Modestine does best – travelling cross country, reaching the parts other camping cars cannot reach. So we left Lagos and headed north by minor roads up into the mountains of the Monchique. This proved to be a delightfully pretty and very rural route, passing through little villages and isolated farms. The road we travelled was poorly maintained being full of potholes and broken verges. It was however, infinitely better than the side roads which were nothing but bumpy, dusty tracks leading out into the deserted hills to tiny hamlets ten or more kilometres away. Frequently we passed old ladies dressed completely in black - with black headscarves even - walking slowly along the road from one part of a village to another. Old men too, busy hoeing their vegetable plots by hand, or driving a mule and cart piled high with grass. Every hamlet we passed here had several little bars or cafes beside the road and all had customers. They are obviously the meeting place for the local community.

Our route wound up into the hills, and we left the villages behind. Here the roadside was lined by eucalyptus trees and mimosa covered in millions of tiny bright yellow pompoms. There were cork oaks, which, as in Spain, had been stripped of their bark, cork being one of Portugal’s major products. There were also plantations of pine trees on the terraced hillsides. Unfortunately, forest fires are not that uncommon and we saw entire hillsides with the blacked, skeletal remains of burned and charred pine trees. Somehow though, the eucalyptus trees seemed more resilient.

Mountain hamlet, Monchique

Mountain hamlet, Monchique Dirt tracks out to distant hamlets, Monchique

Dirt tracks out to distant hamlets, Monchique The result of forest fires, Monchique

The result of forest fires, MonchiqueOur route up here was completely deserted. We stopped frequently as we wound our way higher into the mountains. Always, the only sound was of bees in the mimosa and rarely was there even the distant vista of a tiny hamlet.

Eventually we left the mountains too behind and found ourselves on a bare flat high plateau stretching seemingly forever towards Beja. Here there were cattle, sheep and pigs, all of which have been rarities in the landscapes of Southern Spain and Portugal. Beside the road hundreds of pairs of storks were nesting, their huge untidy homes - bundles of sticks and twigs, balanced precariously on any high pole they could find. A very picturesque scene, but rather ungainly when both birds chose to land on their nest at the same time. The grass covering the red sandy soil was sparse but bright green and where there were rivers they had water in them. Up here too, the air was cooler. The fields gradually gave way to olive plantations and vineyards with occasional citrus orchards. Everywhere the fields were brightly spangled in white and yellow flowers. Spring has definitely arrived in Portugal. There were even trees of bright pink blossoms.

Colony of gregarious storks seen from the car window as we drove past

Colony of gregarious storks seen from the car window as we drove pastAs in Spain, the major roads in Portugal go on for ever without any opportunity to pull off, even for a moment to rest. Roadside cafes and rest areas do not exist here! So we were obliged to keep driving onwards until we eventually turned off at one of the rare surfaced side roads to the little village of São Matias. This turned out to be a very typical Portuguese village with several little streets of tiny, single storey whitewashed houses and literally dozens of little cafes and bars. Basically it seemed as if most villagers had simply turned their front rooms into bars so all their friends could come round for a drink. Probably tomorrow they will all go round to Pedro de Silva’s place instead and on Friday, if he’s not out with his mule, they will take a beer and a smoke with Gonçales Pereira. One thing is for certain here, if they are not named Silva or Pereira, they will be called Lopez, Gomes or Fonseca. There don’t seem to be any other Portuguese names!

The little café we chose in the village was pleasant and unsophisticated with excellent cheap coffee, a huge television in the corner and several workmen enjoying home cooked lunches. Then we went for a stroll around the village and everyone seemed very friendly though, not surprisingly really, we got several odd stares from people sunning themselves in their front doorways, or sitting in groups around the village square.

Around 3pm we reached this campsite at Evora, a couple of kilometres from the town centre. We left Modestine and cycled into town for a couple of hours, parking our bikes just inside the city walls which left us free to explore the network of clean, narrow, cobbled streets on foot.

We only gained an impression of the town today and will return in the morning to explore further. We did see the exterior of the cathedral and the Palácio dos Duques da Cadaval. We also went into the Posada reputed to be the most historically interesting in Portugal. (Posadas are to Portugal what Paradors are to Spain, state-run hotels, generally in old historic buildings such as castles and former monasteries.) There are the remains of a Roman temple and a very nice 18th century building housing the public library. Jill will leave Ian to describe this as he’s bursting to do so….

Cathedral, Evora

Cathedral, Evora Roman temple, Evora

Roman temple, EvoraJust by the Temple of Diana was the public library in a fine baroque building, hung with banners celebrating its 200th anniversary. We were asked to leave our rucksack in a locker and climbed the staircase to emerge in a long gallery lined floor to ceiling with early printed items in locked cases. They appeared to be largely works of theology and canon law but there were various historical works. Ian noticed a work on international law by Selden of Oxford fame. There is also reputed to be an important collection on the Portuguese expansion tucked away somewhere. Many volumes had suffered badly from bookworm. An attempt had been made to reinforce the bindings with brown paper at some stage, but this too had been eaten through. There was no evidence of any public access computer catalogue and the card catalogue on the landing seemed very selective. The reading room had tables with green glass lampshades and bent-wood chairs, altogether a time-warp. At the end of the room a door led into a further gallery, also lined with old tomes, but this time with a labyrinth of shelves in the middle with modern books, classified by UDC. Injunctions to place books consulted in trolleys and not to attempt to reshelve them may have been an admission that the classification was too complex for your average public library – or maybe staff just wanted to reassure themselves that the books were actually being looked at. It seemed a wide-ranging selection with many duplicate copies, mainly paperback and in excellent condition. In fact they seemed to have been rarely opened and the whole library was hardly awash with users. The children’s section included a beginner’s guide to Hegelian philosophy! Clearly they make considerable demands on young minds here – perhaps they had frightened them all away.

Public Library, Evora

Public Library, EvoraThere are absolutely no food shops in the centre of the town. We searched amongst scores of shoe shops, pharmacists, cafes and bars but nowhere could we buy any bread. Eventually our persistence was rewarded in a tiny dark kiosk of a shop off a side street near the church of São Francisco in one of the suburbs. The place was run by an elderly gentleman who talked to us quite happily in Portuguese and we had no trouble understanding each other as he described how a particular bread was made and assured us we’d like it.

Church of São Francisco, Evora

Church of São Francisco, EvoraWe peddled back to our campsite, our appetites whetted to explore Evora in more detail tomorrow. It certainly is an exceptionally attractive university town with a great deal of history behind it.