Map of Stevenson’s journey with Modestine in 1878

Map of Stevenson’s journey with Modestine in 1878If this is not legible on the blogsite it can be copied for consultation separately

Tuesday 25 October 2005, Mende, Lozère (continued)

We had started our journey almost one month later than Stevenson and, so late in the year, the roads were empty of visitors. Our way wound on by-ways across an undulating landscape with pine-covered hilltops and higher mountains in the misty distance. Buildings were constructed in volcanic stone and there were dry-stone walls separating the fields and lining the roads. We passed through the village of St. Martin-de-Fugères where Stevenson had seen the church “crowded to the door, there were people kneeling outside on the steps, and the sound of the priest’s chanting came forth out of the dim interior”. When we passed through today the village was deserted but we were able to admire the striking gothic doorway to the little church.

St Martin de Fugeres, church door – no longer crowded

St Martin de Fugeres, church door – no longer crowded View down to the valley of the Loire

View down to the valley of the Loire The route continued along the higher ground before dropping steeply down into the village of Goudet, beautifully situated on the upper reaches of the Loire and hemmed in by the steep surrounding hills. By a small square there was a Romanesque church with a round tower and the ruined Château Beaufort stood on a rocky outcrop on the other side of the valley. Goudet also proudly housed a cleverly named Archaeo-Logis, a study centre, closed when we passed through, but which offers an interesting series of lectures and other activities connected with the local geology and archaeology.

Goudet Church

Goudet Church Goudet, Chateau Beaufort

Goudet, Chateau Beaufort Goudet

GoudetStevenson had found that “On all sides, Goudet is shut in by mountains; rocky footpaths, practicable at best for donkeys, join it to the outer world of France.” Since then, the highway engineers have been active and perfectly good roads lead into and out of the village, up the “interminable hill” along which Stevenson had urged the reluctant Modestine, onto an open plateau above the river valleys. We passed through Ussel, where poor Modestine’s pack finally keeled over and dangled below her belly. Stevenson was making for the Lac du Bouchet but got lost and never made it. Armed with our Michelin atlas we were more fortunate and arrived in our Modestine at this perfectly circular volcanic crater lake, formed some 300,000 years ago. It was surrounded by wonderful woodlands, ablaze with autumn colour.

Lac du Bouchet

Lac du BouchetClimbing out of the rim of the crater we made our way the short distance to Bouchet-St-Nicholas which was where Stevenson spent his first night at the inn “among the least pretentious I have ever visited”. It was here that the innkeeper made him a goad to keep Modestine better under control. We found nothing to detain us in this muddy farming village, so continued across the open plateau along what is today the Route National 88 through Pradelles and on to cross the River Allier at Langogne. Although he spent his second night there, RLS says little about Langogne, but that prolific Devon traveller Sabine Baring-Gould describes it a “a busy little town of the Gevaudan, of some commercial importance … becoming more and more a summer resort”. The drab commercial outskirts by the bridge where we parked discouraged us from further exploration although, on the approach to the station, we noticed what we dubbed “Stevenson’s Rocket”, an 1870 traction engine which had been placed on display.

Langogne, Bridge over River Allier

Langogne, Bridge over River Allier Langogne, Stevenson’s Rocket

Langogne, Stevenson’s RocketBeing unwilling to drive Modestine through the woods to recreate RLS’s wanderings when he was lost on the third evening of his travels, we took the beautiful narrow road which wound through gold and bronze foliage above the little Mercoire river to Cheylard l’Evêque, described by Stevenson as “a few broken ends of village, with no particular street, but a succession of open places heaped with logs and faggots”. Nevertheless some of these granite-walled houses are quite remarkable, one of them with an impressive tower and another being an inn with notices recalling the journey of Stevenson and Modestine – hotels, bars and restaurants along the route are all jumping on the band-wagon.

View into Mercoire valley

View into Mercoire valley Cheylard l’Evêque

Cheylard l’Evêque Cheylard l’Evêque

Cheylard l’EvêqueWe guessed, fortunately correctly, at the road onward over the ridge of hills as there were no signposts, and selected a narrow, steep and winding road which set out almost opposite the inn, coming out high above Luc with the castle far below us surmounted by “a tall white statue of Our Lady, which, I heard with interest, weighed fifty quintals, and was to be dedicated on the 6th of October [1878]”.

View down into Allier Valley towards Luc

View down into Allier Valley towards Luc Luc Castle with statue of Virgin dedicated 1878

Luc Castle with statue of Virgin dedicated 1878Once down in Luc we joined the road with the railway running beside it along the valley south to La Bastide Puy-Laurent. Stevenson comments that it was “the only bit of railway in Gevaudan, although there are many proposals afoot and surveys being made, and even, as they tell me, a station standing ready built in Mende. A year or two hence and this may be another world”. At La Bastide we turned up a side road to the Trappist monastery of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges of which RLS says “I have rarely approached anything with more unaffected terror than the monastery of Our Lady of the Snows” – nevertheless he stayed a night there and survived his theological discussions with the inmates. The complex is austere and functional, prompting Baring-Gould to comment “Their buildings are tasteless”. The monastery was established in the 1850s and on our arrival the most apparent parts of it were the wine cellar, shop and bar. The monks vinify wines from grapes which are grown elsewhere and a talkative Trappist monk sold us a bottle of Vin d’Oc. We also tasted their cakes. After a short glance at the chapel, we returned to our route at La Bastide, past the statue of the Virgin at the entrance to the drive.

Modestine at the Trappist monastery of Notre Dame des Neiges

Modestine at the Trappist monastery of Notre Dame des Neiges Notre Dame des Neiges

Notre Dame des NeigesIt was getting late and we were tired from the day’s travels. We left the RLS trail to drive the 50 kilometres to Mende where there was one of the only all-year campsites in the region. Our route led through the spectacular gorges of the River Lot, but we were being hassled along the fast Route Nationale 88 and were too exhausted to notice much in the gathering gloom. We found a pleasant campsite by the River Lot on the far side of Mende, just beyond a major building site! We drank the holy wine and slept the sleep of the blessed.

Wednesday 26th October 2005, Florac, Lozère

It was wonderful to have hot showers after two days on the road. We were both exhausted from the travelling, the strong winds and the bright sunshine and felt slightly sick – probably a result of the communion wine last night!

It was freezing cold and shady on the camp site but the hills around were topped by bright sunshine. Around 11a.m. we made our way to a huge new Super U supermarket where we restocked Modestine’s larder and purchased lunch which we took back and ate in the warm sunshine beside Modestine in the car park with views of high steep hills ands exposed grey rocks. Lunch consisted of hot civet de sanglier (wild boar stew) with small roast potatoes cooked with onions and lardons. Where would you find that in England? Certainly not in your normal supermarket. The price? 6.70 Euros (less than £5) for the two of us! It was really delicious.

We returned to Stevenson’s route and picked up his journey at Chasseradès, a tumbledown little village where Stevenson had found that “The company in the inn kitchen were all men employed in survey for one of the projected railways”. That railway still runs nearby.

Chasseradès

ChasseradèsWe continued up the Montagne de Goulet along a route marked as “difficile et dangereux” with views down onto L’Estampe. In fact the route today was fine but we can quite believe it would be treacherous in winter snows. The weather was sunny but with a brisk wind that caused clouds to scud up and billow over from the far side of the mountain. (1497 metres.)

View towards L’Estampe from the Montagne du Goulet

View towards L’Estampe from the Montagne du GouletThe route decended down into Le Bleymard before climbing again up to Le Mont Lozère through woodland and out into the boulder-strewn national park of the Cevennes. The area is on the edge of the volcanoes of the Massif Central and is of rose and grey coloured granites. The buildings are all of granite walls and heavy local slate tiles. It reminded us greatly of the moorland areas of south-west England but far more extensive and with beech forests adding bright yellows and oranges to the deeper colours of the pines. Some areas were bare and treeless with massive granite boulders and crags rising out of the dead grass and bracken. There were even dry-stone walls and sheep roaming wild while on the lower, flatter areas, the land had sometimes been cultivated. There were still some of the granite marker-posts mentioned by Stevenson to guide drovers across the wastelands. There is now a winter sports area at Chalet de Mont Lozère complete with ski lifts. Eventually we reached the Col de Finiels at 1548 metres. Stevenson himself would have been walking cross-country at this point and reached the actual summit at 1699 metres. “Behind was the upland northern country through which my way had lain, peopled by a dull race, without wood, without much grandeur of hill-form, and famous in the past for little beside wolves. But in front of me, half veiled in the sunny haze, lay a new Gevaudan, rich, picturesque, illustrious for stirring events…”. We did not continue on foot to reach this point. It was cold, windy and very reminiscent of Dartmoor with its yellowing grass and bare granite rocks.

Le Sommet de Finiels

Le Sommet de Finiels Modestine on the trail of her namesake in the Cevennes

Modestine on the trail of her namesake in the CevennesWe wound our way down the far side of the pass with wonderful vistas of mountains, valleys, crags and rivers. There were beautiful autumn colours from the birches, chestnuts, beeches oaks and pines in the valleys, clothing the slopes of the hills with orange, rust and gold. It was a scenery that would have reminded Stevenson strongly of his native Scotland. Up here of course, there was no sign of habitation.

View into the Rieumalet Valley

View into the Rieumalet ValleyLike Stevenson and his donkey, we followed the river Rieumalet down to where it joined the Tarn at Pont de Montvert a former stronghold of the Camisards. The Camisards were Protestants who fought against the repression of Louis XIV in the first years of the 18th century. Stevenson, with his Calvinist background, chronicles their struggle with sympathy. Baring-Gould, an Anglican vicar, could see that horrors were perpetrated on both sides. But history moves on. The area is still a Protestant stronghold in Catholic France but even in Stevenson’s day Protestants and Catholics lived peacefully together in the Camisard capital at Florac.

Pont de Montvert is a beautiful, peaceful little grey town on the hillside built into and onto the rock, with the two beautiful young rivers flowing through. It is hard to imagine today that this was once the site of a bloody religious massacre when the persecuted Camisards attacked and murdered the cruel Abbé Du Chayla at his house by the old stone bridge in 1702, thus starting a period of severe reprisals against them in the area from 1702-1704. Stephenson notes in 1878 that the house of the Abbé Du Chayla was still standing. Today the only evidence is the arches of the cellars and the garden fronting the river.

Pont de Montvert

Pont de Montvert Remains of the house of Du Chayla

Remains of the house of Du Chayla Pont de Montvert, bridge

Pont de Montvert, bridgeIt was getting late in the afternoon and we planned to return to Mende for the night, it being the only campsite open anywhere so late in the year. So we reluctantly left Pont de Montvert and followed a beautiful route along above the Tarn for 21 kilometres. It was completely deserted. We saw no vehicles and virtually no habitation. Stevenson refers to it as a new road – though even that would have been no more than an unmetalled track at that time, as would have been all the roads he followed. We paused to admire the Castle of Miral perched on a rock above the wooded valley of the Tarn, gold with chestnut trees. We gathered ripe sweet chestnuts to cook later when we arrive near Béziers.

We finally came down into Florac around 5.15pm and discovered a free parking place for camping cars at a pleasant place on the edge of the town with clean loos and wash basins. So we abandoned our plan to drive 30 kilometres back to Mende and settled here. As dusk fell we wandered down to explore the town which seems very pleasant with various fountains and rivers running through, filled with large trout. Down here the weather is warm and we had no need for jackets even at 6.30pm. An elderly man stopped us to excitedly tell us we must be here tomorrow night as the town will be starting its three day soup festival! He was so happy about it. We later saw lots of banners and posters advertising it and there is even an exhibition of “La soupe dans l’art.”

Fête de la Soupe, Florac

Fête de la Soupe, FloracWe returned to Modestine for the night. She looked comically small beside the larger camping cars that had joined her in the meantime and people kept eyeing her in amused surprise.

Modestine and friends

Modestine and friendsThat earlier Devon traveller Sabine Baring-Gould is very unkind about Florac: “It is a very dirty place, originally walled; the houses were so crowded that the streets were contracted to the narrowest possible width. One has to be careful not to walk down them before eight o’clock in the morning, as all the slops are thrown from the windows into the street, and may fall on the head of the incautious passenger; and here no warning call is given … What is cast forth remains where it falls until torrential rains sweep away the accumulated filth of weeks and even months.” RLS was much more positive and mentions its “old castle, an alley of planes, many quaint street-corners, and a live fountain welling from the hill. It is notable besides for handsome women …” All these we saw in a lively, happy little town preparing for its Festival of Soup and, despite our tediously repeated moans about the cleanliness of French streets, we have no complaints about Florac on that score. Certainly no slops landed on our heads and so we agree much more with RLS than with SBG.

Thursday, 27th October 2005, Florac

The morning started overcast and rainy and the whole of the final stage of RLS and Modestine’s journey was undertaken in swirling mist and drizzle. We started along the valley of the Mimente following the RN88 to Cassagnas, a little hillside village looking run-down and desolate in the grey day. However it had seen more exciting times. Stevenson informs us: “Hard by, in one of the caverns of the mountains, was one of the five arsenals of the Camisards: where they laid up clothes and corn and arms against necessity, forged bayonets and sabres, and made themselves gunpowder with willow charcoal and saltpetre boiled in kettles”. Times have also changed with respect to the railways which were being surveyed when Stevenson visited. They have since opened and often closed again. We descended from the village into the valley for a short distance to reach the Espace Stevenson, a restaurant and campsite (both closed after the season), which were located on the site of the former railway station. Elsewhere on our travels today we saw further evidence of disused railway lines, clearly the railways serving isolated communities in France have suffered the same fate as so many branch-lines in Britain.

Cassagnas

Cassagnas Cassagnas, Espace Stevenson

Cassagnas, Espace StevensonFrom Cassagnas our way took us over a rickety bridge and then climbed through forests on a very narrow road covered in leaves with bright metallic tints up to the Plan de Fontmort, a mist-shrouded crossroads in the forest with a monument to the Huguenots, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 1788 Edict of Toleration.

Autumn colours above Cassagnas

Autumn colours above Cassagnas Plan de Fontmort – monument to the Protestants seen through the mist

Plan de Fontmort – monument to the Protestants seen through the mistThe narrow road wound on through the hills to St. Germain-de-Calberte, a larger, livelier village than Cassagnas and the place where Stevenson spent the last night of his journey. We parked in the little square by the mairie under the plane trees and set off under our umbrella to explore. The notice-board by the mairie showed various activities – classes, talks etc – and the community seems to have been spending many years restoring the nearby castle. The quiet village saw violent times in 1702. It was here that the cruel and repressive Abbé Du Chayla was buried after he had been killed in Pont de Montvert, but his funeral was interrupted by news that the Camisards were on their way to take the village “and behold! all the assembly took to their horses’ heels, some east, some west, and the curé himself as far as Alais”. (RLS)

We found an inconspicuous craft shop, the Atelier des Deux Mines, selling bags of chestnut flour where they provided us with welcome cups of coffee. Here we also purchased for three Euros a little booklet Stevenson et Modestine: voyage en Cevennes which listed tourist possibilities, including the hiring of donkeys to recreate all or part of the journey. Further down the village street we found a baker’s and asked whether they had any cakes made with chestnut flour. Not until Sunday when the village is to have its chestnut feast we were told. Apparently it can be used like ordinary flour but is normally mixed fifty-fifty as it is quite heavy. It is very nourishing, we were told, after all we feed chestnuts to our pigs. We found the simple early 19th-century Protestant temple below the village and then set off down the valley of the Gardon de Mialet river.

St Germain de Calberte – Protestant temple

St Germain de Calberte – Protestant templeFor the whole 21 Km to St. Jean-du-Gard the route was a continuous descent through crags, the road often cut into the rock, under overhanging beech and chestnut trees. We entered the mist-filled Vallée Française and eventually came down into St. Jean-du-Gard and the end of Stevenson’s journey. Curiously the first sound we heard as we parked was the braying of an unseen donkey. We searched the town but never discovered where it came from. Could it have been the spirit of Stevenson’s Modestine welcoming ours at the end of her pilgrimage?

There is a large Protestant temple prominently located in a square by the river, but overall St. Jean-du-Gard seemed a dull grubby place on a rainy October day with listless groups of young people hanging around on their half-term holiday and few shops apparent. We did discover the hotel L’Oronge, where Stevenson is said to have spent his last night, prior to selling Modestine for 35 francs and taking the coach to Alais to pick up his letters (today he would look for a cybercafé).

Tower in the Vallée Française

Tower in the Vallée Française In the Vallée Française

In the Vallée Française St Jean du Gard, Hotel l’Oronge

St Jean du Gard, Hotel l’Oronge Thursday, 27th October 2005, Florac (continued)

Our little pilgrimage ended, we returned to Florac along the Corniche des Cevennes, a route which for some 50 kilometres follows the crests of the hills rather than winding along the sides of the valleys. There was a tough climb to reach it and once there, at a height of between 700 and 1,000 metres, we ducked in and out of the low clouds. We stopped several time to admire the views and collect chestnuts. We even saw sheep, with bells round their necks, feeding on the fallen chestnuts. There seems to be a mix of geology here. Granite gives way to schist and then orange sandstone and a huge limestone cliff, grim and north-facing which continues on to dominate the town of Florac. The scenery through the gaps in the trees is everywhere magnificent and unspoiled. The following pictures run from east to west along the ridge and all look northwards towards the cloud-capped hills on the other side of the Vallée Française.

Corniche de Cevennes

Corniche de Cevennes Corniche de Cevennes

Corniche de Cevennes Corniche de Cevennes

Corniche de Cevennes Corniche de Cevennes

Corniche de Cevennes Corniche de Cevennes

Corniche de CevennesWe returned to the same parking place as last night where Modestine joined another fifteen or so camper vans. In the gathering dusk we went down into Florac to enjoy the Festival de la Soupe – the third or possibly the fifth to be held, nobody seemed to be certain.

A special currency was used throughout the festival, the “soupière” worth fifty centimes. For 12 soupières you could buy a special bowl which could be refilled as often as desired over the following three days at no further cost. Ian asked what the exchange rate was for sterling. Impossible we were told! Everyone was really friendly and we found it lovely to see just how happy everyone seemed. With our soupières we bought glasses of wine and beer but pizzas, onion or cheese tartelettes and of course soup were also on offer. We stood watching a band of very enthusiastic drummers all dressed in eccentric headgear – felt hats, green wigs, dreadlocks or turbans. Jill got blue greasepaint on her face after being embraced by a passing clown asking for bisous (kisses). Everyone was happy, children delighted to be allowed up late, and all ages mixed in together. We saw our little man from last night who had told us about the fête and he looked delighted with it all.

As the evening wore on there was a grand bal with music provided by an Occitan folk band with hurdy-gurdy, bagpipes, flute and accordion. It was held under an awning outside the mairie to protect everyone from the continuous drizzle which had persisted all day. Everyone was crushed in tightly together and dancing with whoever happened to be the nearest person. The lively music even had us stamping the rhythm. There was a long farandole, rather like the conga, where everyone joined together in a long line that wound its way around the square weaving in and out amongst the crowd.

Florac, festival de la soupe, press conference and exhibition

Florac, festival de la soupe, press conference and exhibition Florac, festival de la soupe, drummers

Florac, festival de la soupe, drummers Florac, festival de la soupe, the folk band

Florac, festival de la soupe, the folk band Florac, festival de la soupe, dancing to the band

Florac, festival de la soupe, dancing to the bandOn our return to Modestine we slept really well after a full and lovely day despite the weather.

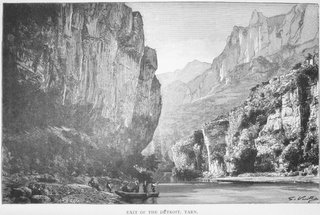

Gorges du Tarn

Friday, 28th October 2005, Aire de Caylac, about 90 Km north of Béziers

We left Florac this morning at about 9 am in the rain and headed down the Gorges du Tarn. As we descended out of the mists the weather improved considerably and we could appreciate the spectacular scenery looking up from the bottom of the gorge. The Tarn was small and fast-flowing, bubbling clearly over the shallow rocky bed bordered by birches, sycamores, oaks and walnuts, still clinging to their bright autumn colours, while the air was filled with blowing specks of gold as the wind whisked swirls of leaves from their branches. Above there rose dark green pines and higher still the grey bare rock.

Gorges du Tarn near Ispagnac

Gorges du Tarn near Ispagnac View towards Prades from above Castelbouc

View towards Prades from above CastelboucAt times we felt very insignificant with the massive cliffs towering above, grey and pink with some sparse vegetation clinging to ledges. In the valley there were tiny medieval villages. On the other side of the river some villages were still cut off from the outside world. In Haute-Rive for example the only contact was by canoe or flat-bottomed boat across the river or a one hour trek along footpaths. Supplies were conveyed across the river by a cable and, as the villagers complained in notices by the winch, despite many years of campaigning and empty promises by the authorities, they were still unconnected to mains water.

Haute-Rive

Haute-RiveThe road had been blasted through the canyon, narrow but with plenty of passing-places. At this time of year there was in any case very little traffic around. In summer there are many campsites open and canoes for hire. It would be wonderful to descend the gorges in a canoe – or on a bike as the route is completely downhill. The cliffs looked very dangerous in places, with folded and fractured strata and rocks fallen all along the base, with small fragments in the road itself – not a place to linger! Sometimes tunnels were blasted through the cliffs, elsewhere the cliffs actually overhung the road. It was among the most spectacular scenery we have ever seen, and bears out the gorge’s reputation as the deepest in Europe, with cliffs normally some 500 metres high. The gorge twists between the cliffs for some forty miles descending steeply towards Millau. The journey took us most of the day, as we kept stopping to wonder at everything.

Tunnel near Château de la Caze

Tunnel near Château de la CazeThere are castles, usually in ruins, and frequently perched high on rocks above the villages. We stopped to admire two of these during the morning. Just beyond the village of Montbrun whose stone houses climb the hillside on the south bank of the Tarn is the castle of Charbonnières.

Montbrun in distance with castle in foreground

Montbrun in distance with castle in foregroundA little further on a lay-by permits one to view the remarkable site of Castelbouc. Sabine Baring-Gould describes it: “a castle in ruins, occupying a tall rock that rises like an isolated block of masonry, with cottages and a chapel clinging to the sides, lest they should slip down into the river. This place can only be reached by a ferry-boat.” There was in SBG’s time still in use “a village oven so vast that when one puts in the bread, by the time you have walked round the oven, you find the bread is baked.” Whether the oven is still in use we did not ascertain but the village can now be reached by a narrow twisting road and a bridge over the Tarn. The site remains extraordinary – it is hard to tell the houses from the stacks of rock that surround them.

Castelbouc

Castelbouc Castelbouc in its wider setting

Castelbouc in its wider settingWe tried to lunch at Ste Enimie but the restaurant we liked had run out of the plat du jour by 1.15, so we picnicked on a rocky ledge by the river just below the old bridge with its massive arch. Above us lay the medieval town, beautifully maintained, with narrow cobbled streets struggling up the hillside and the remains of a monastery at the top. In front of the medieval corn market with traces of half timbering, there was a measure for grain hollowed out of stone. On the hillsides around were the remains of terraces, as there were around many of the settlements along the gorge. The walls of these were now tumbled and they were generally no longer in use. Sometimes by the river, where there was sufficient soil, there were small, carefully cultivated vegetable gardens with enormous tomatoes still clinging to the vines, but generally the sides of the gorge were too steep to support domestic use for vegetables or crops. Baring-Gould was impressed by the site of the monastery but not by the town: “There is but one street in Ste Enimie, exactly 6 feet wide. Should a cart pass through it, one has to jump into the open door of a house to escape the wheels. This street is the town sewer, into which every sort of abomination is cast.”

Ste Enimie, cobbled street

Ste Enimie, cobbled street Ste Enimie, view of terraces from near ruins of monastery

Ste Enimie, view of terraces from near ruins of monastery St Enimie, from Halle du Blé with corn measure in foreground

St Enimie, from Halle du Blé with corn measure in foregroundAmong the grandest landscapes in these gorges are the baumes, vast amphitheatres with towering cliffs caused when enormous subterranean galleries hundred of metres across collapsed in the distant past. The largest of these is the Cirque de Baumes just below Les Détroits, but the Cirque de Pougnadoires about ten kilometres below St Enimie is also magnificent.

Just beyond the Cirque de Pougnadoires is the Château de la Caze. According to Baring-Gould it was built in 1489. When he saw it, it was “in a tolerably perfect condition … four or five hundred pounds would go a long way towards putting the castle into order, in a place where labour is cheap”. This sum has clearly since been laid out, as it is now a select hotel and restaurant, complete with vivid blue swimming pool, and guests are required to have correct attire. In one of the rooms are portraits of “eight beautiful damsels, sisters, all heiresses to this nutshell. It could be reached only by boat or by a goat path down the face of the precipitous cliffs from the desert above. Nevertheless neither river, nor desert, nor precipice could deter suitors, who came, and each returned puzzled to know which of the eight sisters he should take, and how much she would be worth when he got her; and as none of the suitors could make up their minds, the sisters remained old maids to the end.”

Château de la Caze

Château de la CazeThe narrowest part of the gorge begins a little beyond the site of this sad tale. Through Les Détroits the river runs between sheer cliffs a hundred metres high and the road hugs a ledge above them. Above the road other cliffs rear up perhaps 500 metres further with cracked and tumbled rocks, needles and the most fantastic formations.

Les Détroits

Les DétroitsSabine-Baring-Gould writes: “At Ste Enimie one engages boatmen. From this point as far as Les Rosiers the cañon of the Tarn must be traversed by boat, at one time sliding down an easy stream, then floating over a planiol of glassy sheet of almost currentless water, and anon shooting a rapid. The boatmen are very skilful, they perfectly understand their trade, they know every submerged rock that has to be avoided, so that there is in fact no danger, though not a little excitement.”

Boating through Les Détroits in Baring-Gould’s days

Boating through Les Détroits in Baring-Gould’s daysThe last few miles before Millau are still pretty but less awesome than higher up the river. It was later in the afternoon when we reached Millau where our plans to spend the night at the space for camping cars were scuppered when we found all the places were already occupied by the time we arrived, forcing us to continue south in search of somewhere for the night.

While the motorway is free beyond the town, there is a charge if using the impressive slender white suspension bridge which forms part of the motorway that we could see crossing the gorge. We didn’t use this bridge, instead climbing the twisting route up the side of the gorge to join the motorway beyond Millau. We emerged at the top of the gorge onto a sparse grey inhospitable limestone plateau that is almost a desert of scrub wasteland and tumbled grey boulders. It did not even appear to be able to support sheep. This type of landscape is common in the Midi and is locally known as Les Causses. The wind was very strong with horizontal mizzling rain.

A drive of forty kilometres south brought us to this Aire de Caylar. There are several camping cars here too in what is actually a motorway service station for Total fuel with shops, toilets and acres of windswept parking. Ian’s just gone off to buy a bottle of local vin de Herault to help us while away the evening and the friendly couple in the camping car next to us have told us of their lovely holidays in Devon and Cornwall and how they camped two nights at Tintern Abbey in the Wye Valley. It is raining now but we are warm and snug inside Modestine.